On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, Barcelona is putting the spotlight on digital gender-based violence. The debate “A Cybersyn to Democratise Digital Culture,” held at the Canòdrom with the collaboration of Digitalfems last March 8th, had already warned how the music and tech industries reproduce and amplify structural inequalities that must also be named as forms of violence.

Today, November 25th, Barcelona commemorates the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women by focusing on a reality that often remains invisible: digital gender-based violence. The data is overwhelming. 39% of sexist aggressions take place in digital spaces, and in Barcelona one in five teenage girls has suffered online abuse, a percentage that rises to 31.8% among 18-year-old young women.

But digital gender-based violence goes beyond cyber-harassment or privacy violations. It also manifests in more subtle and systemic structures, in the algorithms that decide who gets heard and who does not, in platforms that concentrate power in the hands of a few, in industries that relegate women to precarious visibility while decision-making positions remain inaccessible. Ultimately, it is a digital ecosystem that reproduces and amplifies the same inequalities found in offline society.

The data no one wants to hear

Only 30% of women work in the music industry. Of these, 70% earn less than the average salary and 85% report barriers in hiring. In leadership positions, the number drops to 15%. And if we look at the CEOs in the music industry, only 13.7% are women. In the tech sector, the situation is not much better. Women represent 31%, but management roles barely reach 20%.

These numbers are not just statistics; they are a map of structural violence. Because when 70% of recorded music revenue comes from streaming and women do not occupy decision-making spaces in platforms or tech companies, we are talking about an exclusion that determines who gets paid, who is visible, and who has a voice. And in a context of accelerated platformisation and digitisation of the cultural sector, this becomes a form of economic and symbolic violence that must be named.

Technology serving the people, not big tech

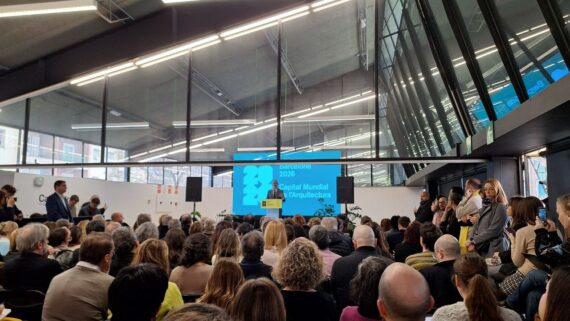

On March 8th, the Grades Obertes at the Canòdrom filled up to discuss how to build a digital music future that does not reproduce gender-based violence. Under the title “A Cybersyn to Democratise Digital Culture”—a reference to the Chilean 1970s project that sought to place cybernetics at the service of democratic planning—four experts addressed the challenges of an industry that continues relegating women to the stage while decision-making remains dominated by men.

Antònia Folguera (XRCB and Sónar) stated it clearly: “It’s hard for women to talk about money, but we must talk about it.” Because behind the precariousness of artists and cultural workers lies a form of economic violence that must be exposed. Men, she reminded us, “tend to have more money to invest in projects even knowing they might lose it.” Women do not.

Natalia San Juan (Femnøise) opened the debate with a utopia: “I want a future for the music industry without gender, where it is not obvious that we are placed somewhere due to quotas but because of our value.” A future where quotas are no longer needed because equality is real, not cosmetic. “Utopia helps us keep moving, but we need to think about the things we can change,” she added.

When visibility is also violence

Kissy Y. Perea (Roots Entertainment Agency) touched a nerve when she said: “We have always been seen on stage, singing or dancing—which is also wonderful—but there are many women producers who want to find other paths to contribute to this revolution.” The hyper-visibility of women’s bodies, often sexualised, goes hand in hand with the invisibilisation of talent and decision-making capacity. “The internet has relied heavily on our physicality as artists without showing our intellectual abilities,” she warned.

This dynamic directly aligns with what this year’s institutional 25N declaration identifies as “aesthetic pressure on women’s bodies,” a form of gender-based violence that “is often amplified by media and digital platforms, limiting rights and freedoms, harming physical and psychological health, and conditioning full participation in all spheres.”

Lara Alcázar from the MIM Association framed it in a broader perspective based on data from a study highlighting the underrepresentation of women in decision-making roles: “With the underrepresentation of women, care disappears. They talk about consumption instead of art.” An industry that treats music as merchandise is an industry that reproduces violence. But, she warned, “through data, research, mobilisation, and work ethics, change is possible.”

Biased algorithms, concentrated power

When you open Spotify, you are greeted with recommendations you didn’t ask for—algorithms deciding what you should listen to. “I would like the platforms we use to listen to music to be ours, not big tech’s,” argued Antònia Folguera. Kissy added that alternatives exist, such as platforms with algorithms prioritising emerging artists, but more spaces and more training are needed to make them visible.

Natalia San Juan summarised it well: “Beyond platforms and their biases, the problem is that there are not enough women producers.” Because without women creating from the ground up, algorithms will continue reproducing the same biases, the same exclusions, the same forms of violence. And this is where metadata sovereignty comes in—the core theme of the entire March 8th event at the Canòdrom.

Metadata, the invisible power that determines who gets paid

Metadata is the information that accompanies each song—who composed it, who produced it, who holds the rights. It is invisible to listeners, but it determines who gets paid and who does not. In an ecosystem where 70% of revenue comes from streaming, control over metadata is power. And like so many other forms of power in the music industry, it is unequally distributed.

The debate raised uncomfortable issues such as the precariousness of freelance regimes, the urgent need for training in algorithms, networking, marketing strategy and legal rights. “We need to make things easier for emerging artists,” insisted Kissy, pointing out that the challenges are economic but also educational. Lara advocated for non-mixed spaces where women can meet, share strategies, and build alliances without having to constantly justify their presence.

From denunciation to action

This year’s 25N institutional declaration is clear: “Denying digital violence or making it invisible is also a form of violence. The digital sphere is not separate from society—it’s just another space, but with less regulation and constantly evolving dynamics that reproduce and amplify structural inequalities.”

In this context, initiatives such as the March 8th event at the Canòdrom, which under the slogan “Music, Metadata and Digital Feminism” promoted the digital empowerment of women in the music industry, show how we can move from denunciation to action—how we can build safe, violence-free, trust-based digital environments.

The event closed with concerts by GIGI ROS and Fernanda Alemany, who reclaimed the role of women in music from the dance floor. Because the digital feminist revolution is also danced, sung, and lived. “A thousand heads think better than one,” said Kissy. And from this multiplicity of voices, data, movement, and ethics, we build a revolution that leaves no one behind.