The platform economy is an economic model in which transactions and value creation are carried out through digital platforms. This model has changed the landscape of labour relations, introducing new forms of work such as freelance work and the gig economy, or working for gigs or one-off assignments.

In recent years, we have witnessed an immense explosion of digital applications and services centered around big data and predictive systems. These algorithm-based systems possess the capability to process vast amounts of information, learn, operate autonomously, or even provide direct guidance in various situations. The fourth sesion of the “IA, Drets, Democràcia” series delved into the profound transformations occurring within the realm of work, serving as the vanguard of change in labor relations.

The paradigm of labor has undergone a fundamental shift. An increasing number of individuals now offer their services through digital platforms, and all indications point to a continuous rise in this trend. This ongoing transformation has given rise to a new form of capitalism based on the digital economy, leading to novel modes of work, the offshore outsourcing of labor, and the casualization of work, accompanied by heightened surveillance. We are presently confronting a reorganization of the system on an unprecedented scale.

In this platform-based economy, digital platforms such as Uber, Glovo, or Deliveroo continue to establish themselves without adequate scrutiny, often lacking digital sovereignty, thereby effectively privatizing substantial portions of the public sector. But what about the workers? Frequently, they are engaged as freelancers or independent contractors, rather than traditional employees, potentially resulting in diminished labor protections and rights violations.

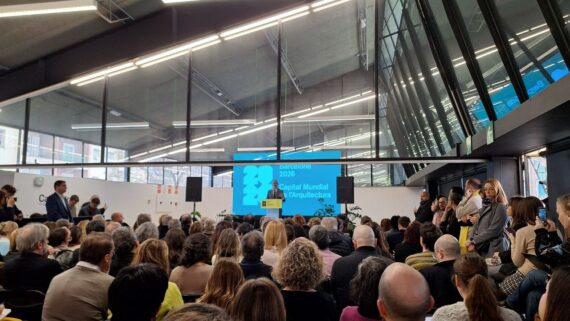

These concerns, alongside others, constituted the focal point of the fourth session of the IA, Drets, Democràcia” conference series held at the Canòdrom – Ateneu d’Innovació Democràtica de Barcelona. Speakers included Anna Ginès Fabrellas, a professor in the Department of Law at ESADE and director of the Institute of Labor Studies; Sergi Cutillas, an economist specialized in competition policy, digitalization, and strategic consulting and a member of the Observatory of Labor, Algorithm, and Society; and Daniel Cruz Fuentes, head of Analysis and Digital Transformation at CCOO Catalonia.

Social Control and Work Process Monitoring: Risks and Opportunities

A study titled “La Plataformització del trabajo,” published by the Joint Research Center of the European Commission, highlights the presence of algorithmic management in work settings. In Spain, this phenomenon impacts 35% of the population, nearly 20% of whom are subject to automatic assignment of work shifts or other job-related processes through algorithms and digital devices.

The integration of artificial intelligence into labor relations is far from science fiction. With the proliferation of new technological products and services, numerous companies are already utilizing predictive systems driven by decision-making algorithms. These algorithms are responsible for tasks such as hiring personnel, allocating tasks, determining salaries, and even initiating terminations. “While I personally believe that these systems can bring significant business advantages by expediting decision-making and enhancing organizational efficiency and competitiveness, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the employment of smart technology today presents substantial challenges and risks to fundamental human rights,” explains Anna Ginès Fabrellas, a Professor in the Department of Law at ESADE and the Director of the Institute for Labor Studies.

As early as 2017, concerns were raised about the adverse impact of artificial intelligence on basic human rights. One of these concerns pertains to the violation of an individual’s right to privacy. These models implement robust surveillance systems to gather data and delineate worker behavior, ultimately predicting personal information. “The most sensitive data can reveal highly intimate details about individuals,” asserts Ginès. A mere analysis of Instagram or Facebook likes can predict information such as gender, racial background, political opinions, religion, intelligence levels, and even overall happiness.

The second workplace impact pertains to equality and non-discrimination. “Consider Apple’s personal assistant, Siri, which initially responded to derogatory language with submissive responses. While the company eventually revised this response, it inadvertently perpetuated a submissive portrayal of a woman who acquiesces to insults,” elucidates Ginès. Similar issues are observed, for example, in facial recognition systems affecting Asian individuals, where the machine requests them to open their eyes wider, assuming that their eyes are closed. Gender stereotypes and biases are widespread in the technology industry due to the lack of a gender and racial perspective in product design.

A third consequence involves algorithmic discrimination, stemming from variables, databases, or proxy variables within the algorithm. In terms of variable-based discrimination, a case emerged where Deliveroo’s algorithm exhibited bias, favoring individuals who were more active during peak hours while penalizing those who selected less congested time slots. Another instance involved Amazon’s withdrawal of an algorithm used for staff selection, which exhibited a bias towards male candidates, reflecting the company’s male-dominated hiring history.

Algorithmic Mediation, Impact, and Regulation

One sector exemplifying the profound effects of the platform economy is transportation, particularly the taxi industry. In 2014, a new player, Uber, emerged, presenting itself as a harbinger of the future with a collaborative, peer-to-peer economic model. “Beneath this enticing facade, we witnessed a multi-million-dollar company employing a progressive narrative to circumvent taxi regulations, cloaking its actions in modern rhetoric,” notes Sergi Cutillas, an economist specializing in competition policy, digitalization, and strategic consulting, and a member of the Observatory of Labor, Algorithm, and Society (TAS). In response, the taxi sector mobilized, culminating in a 2017 ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union in favor of the taxi industry.

A significant point of contention emerged surrounding VTC (Vehicle with Driver) services, enabling users to book chauffeur-driven transfers. The emergence of platforms led to multiple clashes with the traditional taxi sector. However, the Spanish government recently passed a new decree law, effective as of June this year, to regulate VTC services. The decree introduces environmental and traffic management criteria, aiming to restrict the issuance of licenses utilized by platforms such as Uber, Cabify, or Bolt, while designating the services as of “public interest.” The regulation empowers Autonomous Communities to impose limitations on these licenses.

Although Barcelona provides a relatively successful case in this regard, an offensive from these platforms is presently underway. These platforms have accused Èlite Taxi, a Professional Taxi Association advocating for the rights of taxi drivers, of cartel-like behavior. Similarly, the Free Now platform, a collaboration between BMW and Mercedes, initially positioned itself as a defender of taxi drivers’ rights but has since challenged regulations by asserting its status as an information society company, thus evading certain taxi sector regulations. Consequently, their algorithmic system incentivizes workers who align with their vision of a model taxi driver.

The TAS Observatory is actively working on defining the role of digital transport operators and incorporating aspects such as explicability. “The focus of trade union efforts is reintegration, as this activity should not be vertically isolated from the broader enterprise,” emphasizes Cutillas.

Response of Union Movement: Balancing Digital Platforms and Artificial Intelligence

The traditional union movement has faced challenges in comprehending this novel business model. The advent of societal “uberization” and the Amazon model has propelled the platform economy into the spotlight, ushering in new realms of work that capitalize on this transformation. CCOO Catalonia identifies three distinct categories: false self-employed individuals promoted by companies like Uber, Cuideo, or Glovo; freelancers utilizing intermediary platforms within the gig economy, such as Fiverr, Uptowork, or Malta; and self-employed professionals operating on platforms like TaskRabbit, Abogadea, or Top Doctors. “Our focus must be on combatting the false self-employed model, as it undermines established business norms,” clarifies Daniel Cruz Fuentes, Head of Analysis and Digital Transformation at CCOO Catalonia.

A staggering 54% of individuals acknowledge experiencing digital fatigue. CCOO Catalonia has embarked on an initiative to explore how digitalization impacts the labor landscape. “We must delve deeper to enable agreements that regulate the right to digital disconnection, the use of company devices for non-work activities, and the implementation of geolocation systems,” Cruz asserts. The European Commission has spent two years deliberating the criteria for the platform directive, aiming to curtail digital platform abuses and enhance working conditions. Yet, these efforts have proven insufficient.

The current draft of the directive proposes seven criteria for determining whether platform workers are classified as employees rather than self-employed individuals. All seven criteria must be satisfied for the platform to be recognized as the employer. “In Catalonia, the trade union movement has made significant strides in this area, initially engaging platform workers through specialized workshops, offering support during protests, engaging in lobbying efforts, and assisting in trade union elections,” elaborates Cruz.

Unresolved Challenges

The path forward entails the pursuit of ethical and equitable artificial intelligence. Legally, greater prominence must be given to data protection regulations, with increased transparency and individual rights regarding algorithm behavior, accompanied by mandatory external algorithmic audits.

On a technical level, the composition of technological design teams must become more diverse, with efforts to minimize bias and enhance transparency and comprehensibility. Ethically, we must avoid succumbing to technological determinism. Facial recognition, emotion detection, and mental state analysis systems should be prohibited in workplaces. “We must develop streamlined AI systems and more straightforward models. There exists ample room for artificial intelligence to be both advanced and equitable while upholding fundamental human rights,” concludes Ginès.